27 Jun Slump in Kiwis becoming Aussie citizens

A recent research shows there has been a slump in the number of Kiwis becoming Australian citizens since a law change in 2001. Data shows out of 146,000 New Zealand-born migrants who arrived in Australia between 2002 and 2011, only 8.4 per cent of them were citizens by 2016. The numbers are even lower for New Zealand-born Maori, with less than 3 per cent becoming Australian citizens, according to research from Victoria University’s school of Maori studies.

Meanwhile, New Zealanders who arrived in Australian between 1985 and 2000 had citizenship uptake rates of nearly 50 per cent by 2016.

The research, by Te Kawa a Maui’s Paul Hamer, finds the low numbers are due to restrictions imposed in 2001 that removed the eligibility of Kiwis from applying directly for citizenship unless they had a skills-based permanent visa.

NZ versus other nationalities

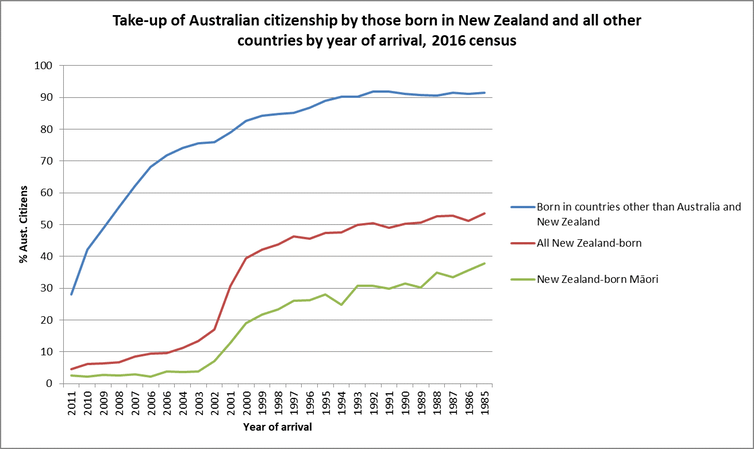

This stands in contrast to other settlers in Australia, for whom the acquisition of a permanent visa usually becomes a stepping stone for entry to the country. The cumulative impact of this exclusion of New Zealanders becomes clear in the 2016 Australian census results. The following graph indicates the take-up of citizenship after the qualification period of four years.

We can see that, over time, almost all settlers from third countries become Australian citizens. Those born overseas (excluding New Zealand) who arrived between 1985 and 2000 have take-up rates of citizenship of 80% to 90%.

New Zealanders have always had a much lower take-up rate because citizenship had little bearing on their rights before the 2001 legal change. Of the New Zealand-born people arriving in Australia between 1985 and 2000, only 40% to 50% have taken up citizenship – roughly half the rate of those born in other countries.

But since 2001, the access of New Zealanders to Australian citizenship has almost collapsed. This is especially so for New Zealand-born Māori, who are less likely to be able to meet the skills requirements or the cost of a permanent visa.

If we take the year of arrival of 2008 as an example, we can see that 55.5% of those born in third countries are Australian citizens. However, only 6.8% of all New Zealand-born migrants who arrived that year are citizens, including only 2.5% of Māori.

Contrast with a decade ago

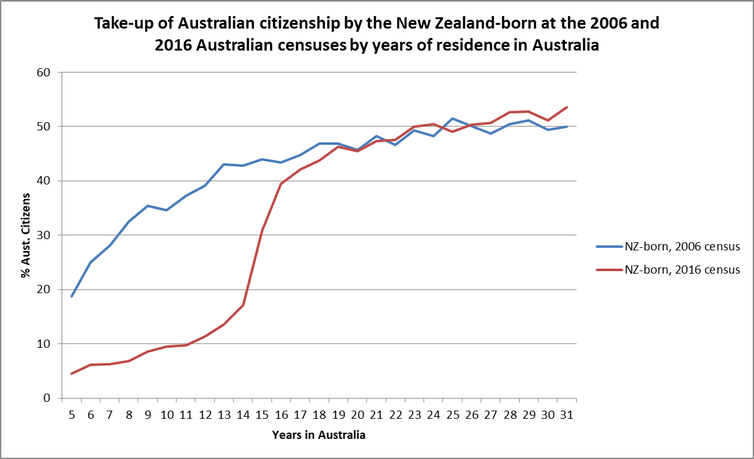

To make sure that this drop off among recent migrants is not a particular feature of New Zealanders’ take-up of citizenship in Australia, we compared the 2016 census results with those of 2006.

We can see that, in 2006, there was a much more gradual decline in the take-up rate of Australian citizenship by New Zealanders among more recent arrivals. There was no sharp dog leg in the line as in 2016.

This confirms that the 2001 law change has caused the take-up rate of citizenship by New Zealand migrants to drop dramatically.

In 2001, the Australian government considered that about 40% of New Zealand settlers would qualify for a permanent visa, and thus be able to go on to acquire citizenship.

The reality is, however, that far fewer have applied. The census data show that more than 220,000 New Zealand-born migrants have arrived in Australia since 2002, following the law change. However, according to Department of Social Services data, only 14,500 permanent visas have been granted to this group over the same period.

Many are likely deterred by the expense and uncertainty of the process. A base application fee is A$3,670 for an individual and, with associated costs, it would set a family of four back more than A$10,000.

Critics of the government’s currently proposed amendments to citizenship law argue that they are unjustified and will do little for social cohesion. Peter Hughes, a former senior official in the Department of Immigration, described them as

… turning the whole inclusive idea of Australian citizenship since 1949 on its head.

It is timely to remember that the single biggest exclusion of Australian citizenship since 1949 arguably occurred in 2001, and that New Zealanders in Australia continue to live with its consequences.

No Comments